Meet the PCAPS SG: Reflections from PCAPS SG member Gita Ljubicic on improving weather and ice services for Inuit communities

This month’s Meet the SG blog post features PCAPS SG member, Gita Ljubicic, who is a Professor in the School of Earth, Environment and Society at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada. Gita is a geographer with training in the natural and social sciences. Her work is driven by a deep commitment to respecting and learning from Indigenous knowledge alongside science to address complex social and ecological challenges. Gita and her StraightUpNorth research team are dedicated to a cooperative, community-engaged approach to research that involves developing and fostering working relationships with Indigenous experts and organizations throughout all stages of the research process. Within PCAPS, Gita contributes her social science experience, and perspectives from working with Indigenous communities, to inform more user-driven design so that polar prediction services can be more relevant, accessible, and useful.

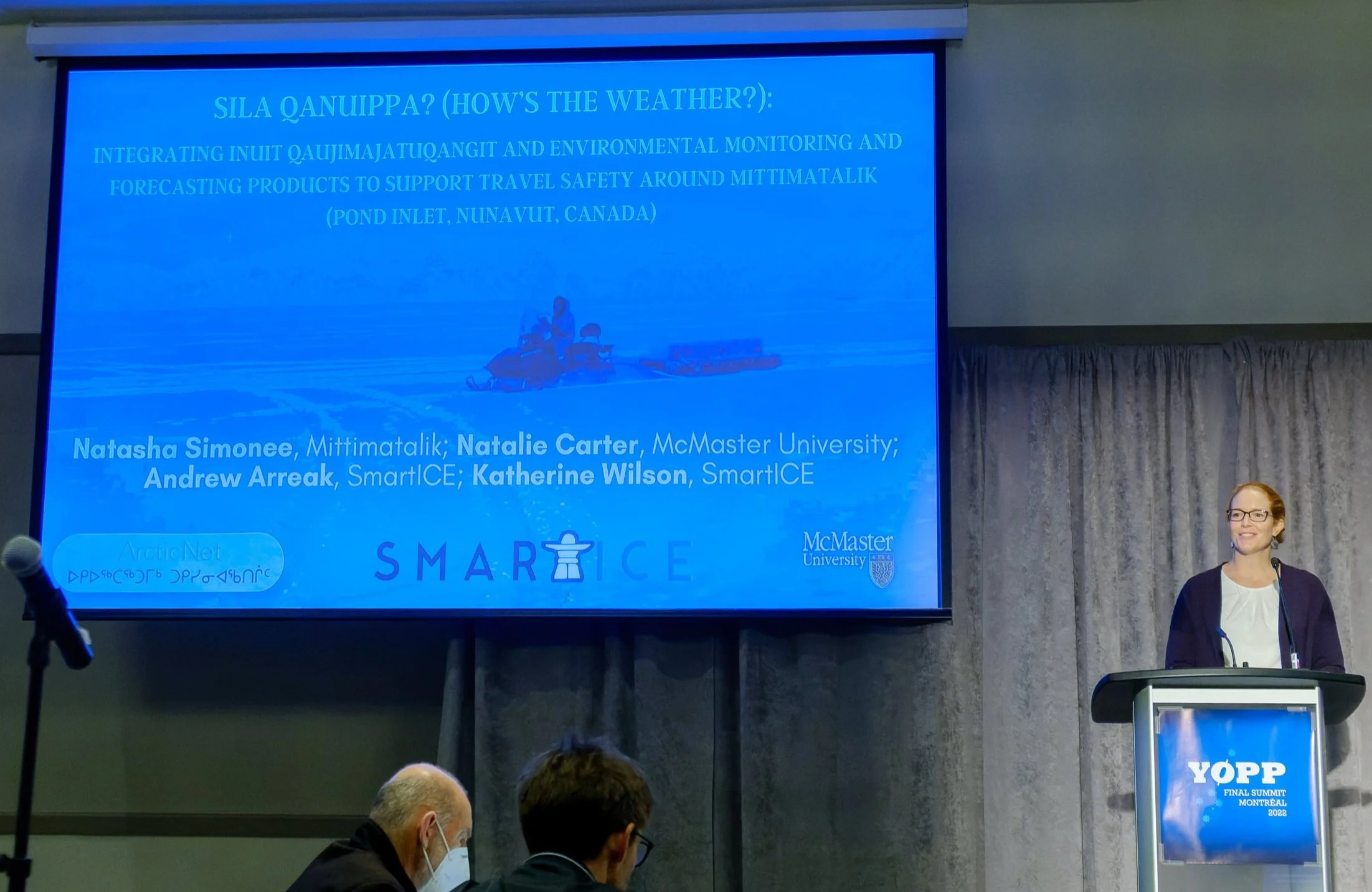

Gita facilitating the YOPP Final Summit plenary panel session on “Societal and Economic Implications: Canada” (August 2022). Photo credit: Neil Gordon

My first opportunity to go to Nunavut was as a Master’s student in 2001. I had grown up in Ottawa – Canada’s capital city – and had never liked the cold or camped outside of a campground. I was to spend the summer camping on the tundra, learning about tundra vegetation to connect with satellite imagery. Myself and two other students (with a similar lack of Arctic field experience) were dropped off by a small twin otter plane on a riverbank in the middle of Boothia Peninsula with all our gear for the summer, with the promise of returning to pick us up in two months. I figured by the end I would love it or hate it. Since I’m writing this blog, I’m sure you’ve already guessed that I loved it!

The 24-hour sunlight was energizing, the vast spaces were inspiring, the animals were delightful, and I had many hours alone doing field work where I reflected on all sorts of things. It was a life-changing experience for me!

Caption: Gita Ljubicic (Laidler) during her Master’s research on Boothia Peninsula, Nunavut (July 2001). Photo credit: Craig Sheriff

By the end of the summer I knew I wanted to continue doing Arctic research, but I wanted to work more with people – with the Inuit whose homelands I was on – and to do research that could have some benefit for Northern communities.

Gita working with Elders and interpreters documenting Inuktitut sea ice terminology during her PhD research in Kinngait, Nunavut (March 2008). Photo credit: Karen Kelley

After completing my MSc, I continued in school to pursue a PhD, but switched from physical to human geography, and to more of a marine than terrestrial focus. Now, nearly 24 years later, I lead the StraightUpNorth (SUN) research team at McMaster University. We are an interdisciplinary team of northern- and southern-based researchers dedicated to addressing northern community priorities and supporting Indigenous self-determination in research. We work with Inuit, Métis, and First Nations communities across the Canadian North, including: Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Nunavik (northern Québec), and Nunatsiavut (northern Labrador). We follow a community-engaged approach to research, tailored to local and cultural contexts of our research partners. We address a range of environmental issues based on community-identified priorities. Our collective goal is to bring diverse perspectives and evidence together to inform more representative decision-making, particularly related to: environmental monitoring, wildlife co-management, education, cultural heritage, Inuktut language, and northern research policy.

In an Inuit knowledge context, knowledge must be shared and applied to be of value. Thus, we aim for all results of our research to contribute to the common good.

Theo Ikummaq teaching Gita about spring sea ice travel safety during her PhD in Igloolik, Nunavut (June 2005). Photo courtesy of Gita Ljubicic.

My involvement with the WMO began in 2015 when I was invited to join the Polar Prediction Project Societal and Economic Research Application (PPP-SERA) Task Team. I served on that team for 8 years, learning so much from fellow members, along with diverse stakeholders we met in Ottawa, Christchurch, Fairbanks, Wageningen, and Punta Arenas, prior to turning more virtual during COVID. I led the ArcticNet-funded and Year of Polar Prediction (YOPP)-endorsed project “Understanding Inuit Uses and Needs for Weather, Water, Ice, and Climate Information and Services in Nunavut, Canada”, and also served on the YOPP Final Summit Scientific Program Committee.

In Canada, as in other countries in the Circumpolar Arctic, weather, water, ice, and climate (WWIC) information services have been designed, managed, and coordinated according to the standards and priorities of lower (southern) latitudes. There are very few northern-based instrumental observations to inform regional forecasting services; most are located at community airports, with hundreds of kilometers between stations. Approximately 50,000 Inuit live within and near Inuit Nunangat (Inuit homelands in the Canadian Arctic), and they continue to travel on the land, water, and ice in all seasons for harvesting country food, cultural practices, and to go between communities. Inuit are increasingly seeking out weather, water, ice and climate (WWIC) information and services to inform their travel decisions due to a combination of:

rapidly changing, less predictable, and extreme environmental conditions due to climate change;

limited community-relevant environmental forecasting services/products; and

fewer community members with extensive land-based knowledge and experience.

However, available WWIC products and services are not easy to access, understand, or use in many communities, and they are not always relevant or accurate to the local conditions of interest.

Boating during break-up in Pangnirtung, Nunavut (June 2008). Photo credit: Gita Ljubicic

Some of our key partners are leading innovations in developing their own products to meet their unique needs, such as: SmartICE, Ittaq Heritage and Research Centre, Aqqiumavvik Society, SIKU (Indigenous Knowledge App), Coastal Labrador Climate and Weather Monitoring Program, and Silaniarviit. Much can be learned from these and other Inuit-led initiatives to inform Polar Prediction services at regional, national, and global scales.

Collaborative analysis workshop with our ArcticNet/YOPP project team in Arviat, Nunavut (October 2021). Photo courtesy of Gita Ljubicic.

As we learned in PPP-SERA, there are many diverse user groups across both polar regions, seeking to use WWIC products and services that can inform their decisions regarding travel safety as well as to ensure economic prosperity and ecological health. The Open Sessions we hosted, and our Task Team research activities, helped to document the specific needs of ship captains, fisheries managers, tour operators, field research managers, pilots, military personnel, among others. The context is very different in the Arctic, where there are diverse geographic and cultural considerations related settlements and livelihoods, from the Antarctic which is focused on research, tourism, and fisheries operations (albeit varying across jurisdictions within the Antarctic Treaty countries).

As PPP ended, I was happy to be invited to be part of the PCAPS SG. It is a welcome opportunity to continue expanding work we started during YOPP. The addition of the “S” for “services” in the PCAPS acronym was partly an outcome of YOPP Final Summit discussions. The science-to-services transformation was recognized as being critically important if technological and scientific improvements in WWIC forecasting and modelling are to be of value to – and useable by – the anticipated users of WWIC products and services. As a social scientist within the SG, I work with my colleagues to ensure consideration user needs throughout all stages of research, as well as WWIC product design and delivery. This takes time, requires strong relationships with user groups, and requires skills to translate user feedback into model and forecast refinement and improved user interfaces. However, as our Inuit colleagues continually emphasize, we need to use the best available knowledge to make travel safety decisions. Working together, improvements in WWIC products can save lives.